Ho scritto un articolo sul nuovo forum per gli appassionati di ceramica italiana. Treni e tazzine da caffè, una accoppiata particolare!

Categoria: Pottery

-

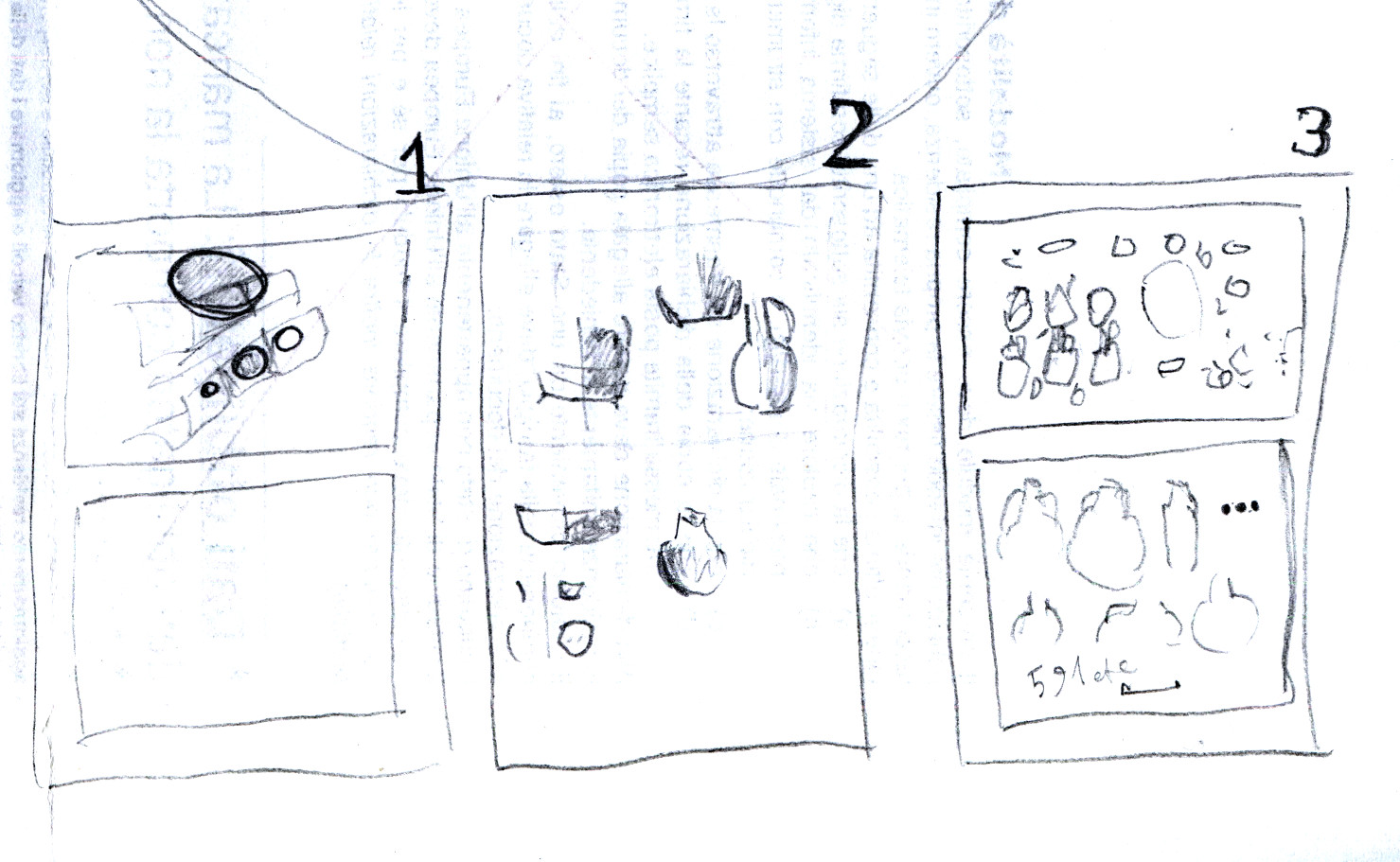

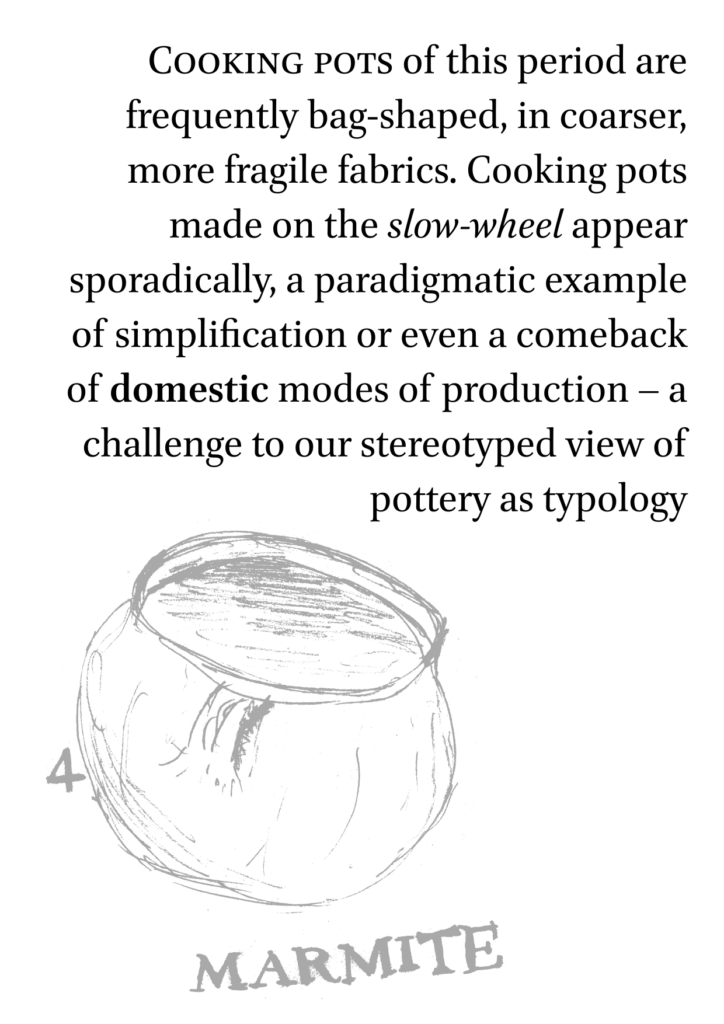

Interlude pages for my PhD thesis (with sketch drawings!)

Who said PhD theses have to be boring texts with horrible typography?

Even if my thesis is far from being ready for discussion, I can’t help some diversion from the actual writing. Today I put together this experiment for an interlude page: imagine you’re skimming through dozens of pages and suddenly your eyes catch something different: a short sentence at font size 36, coupled with a rough sketch drawing of a Byzantine cooking pot, or the interior of a cellar where a young girl is walking to bring wine to the table.

The drawings are mine ‒ pencil on pieces of recycle paper with minor passages of digital editing and vectorisation. You may like them but they’re not sketchy for an artistic choice, that’s just the best I am able to do with my bare hands. Some practice might help, I am told.

The drawings are mine ‒ pencil on pieces of recycle paper with minor passages of digital editing and vectorisation. You may like them but they’re not sketchy for an artistic choice, that’s just the best I am able to do with my bare hands. Some practice might help, I am told.The text is typeset in the Brill font, that is only free for personal use, but I like it and I wanted to experiment. Alegreya, Linux Libertine, Source Serif all look good on that page, too. I think it needs a serif font.

Does this bring more value to the surrounding pages? I’m not sure, to be honest. It could be said that they distract from the actual content, that is supposed to be of academic value, and that this kind of page layout is best left for architecture and design magazines. However, not everyone is going to read your PhD thesis from cover to cover, and a bit of typographic color here and there will not hurt.

-

GQB 2015, day 9: wrap up, iterate

Friday 17th July is the last day at work in this short GQB 2015 field campaign. I’m still a bit exhausted from the return trip to Rethymno, but most importantly I’m very satisfied with the exchange of ideas about various topics (Early Byzantine fortifications, water supply systems, pottery, exploitation of natural and agricultural resources) that we had.

Since my main task here was to work on the analysis of ceramic contexts, I just continued my writing of text and R source code as in the past days. In the late afternoon we left to pay a short visit to the village of Panagia where we found an old water fountain that is depicted in a 100-years old photograph. It’s strange, photographs seem to tell true stories, so direct ‒ whereas in fact they’re a paradigmatic form of mediation. Sometimes, when you need to get a better understanding of an object, it’s useful to look at it from different angles, at different scales, alone or in its natural context, under a microscope or in your bare hands. I think that’s what I’m trying to do with the ceramic contexts from the Byzantine District of Gortyna: it’s not always easy and of course it’s not always working because I lack the archaeological, statistical, petrographic, drawing skills that would be needed to make this “prism” fully working. However, I am convinced that the result is worth the trade-offs, and there will be room for improvement of the details at a later stage. For now, I just go on iterating, half artificial intelligence algorithm and half craftsman.

-

GQB 2015, day 8: DynByzCrete, οι πρωτοβυζαντινοί οικισμοί της Κρήτης

On 16th July we’re out of the Mesara to join a study seminar about the Early Byzantine settlements of Crete, organised by the Institute of Mediterranean Studies (FORTH-IMS) in Rethymno as conclusion to the DynByzCrete research project led by Christina Tsigonaki and Apostolos Sarris. I was really happy to meet other colleagues I’ve met before in various parts of Europe: Kayt Armstrong, Anastasia Yangaki, Gianluca Cantoro. Yesterday I posted the summary of my talk, apart from the conclusions.

I had the privilege of being the last speaker, and taking advantage of the fact that Anastasia Yangaki had provided a detailed overview of ceramic consumption and production in Crete from the 4th to the 9th century, I could point to some specific issues in how we date archaeological contexts with pottery and most importanly in how we prioritise ceramic studies. Ceramic specialists are a rare species, and until now we have failed to provide the means for other archaeologists to quickly identify characteristic type finds of the Early Byzantine period, with sufficient detail to avoid very generic chronologies like “5th-7th” and “8th-9th”, that are highly problematic. We also have a responsibility for the fact that studies and publications of ceramic finds are always lagging behind fieldwork, because 1) there is little selection of significant, well-dated stratigraphic contexts 2) and the study and publication have been for too long done by separating ceramic productions that were looked at separately by hyper-specialists, rather than looking at contexts as our atomic unit. Therefore, it has been impossible to provide the quantified ceramic data that are needed for the type of analytical work that it envisaged by the DynByzCrete project – and we should admit that this data will be unavailable for a long time. As a thought experiment, we could stop doing fieldwork for 25 years and dedicate most of our efforts to the study of all significant ceramic contexts from recent rescue archaeology.

If we agree that there is a potential for extracting information about social dynamics from pottery, can we also agree that provenance studies based on standardised archaeometric procedures are only one of many ways that this can be done? We know very little of the actual manufacturing of most pottery types, of the material culture that permeates their making and usage. So, taking a broader view at the DynByzCrete project, while the environmental determinism behind some of the geospatial analysis needs to leave room for the complexity of Byzantine societies (plural), it is clear that we are at a turning point in the way we look at Early Byzantine Crete, and that’s because we are starting to consider the island in its entirety instead of focusing on a single settlement, no matter how large or important. In this respect, regional surveys don’t seem to provide a qualitative advantage over prolonged excavations – and their multi-period focus is an opportunity to deal with longue durée patterns but also a rather discomforting exercise in oversimplification of changes in historical periods. Pulling an amazing variety of data, that are mostly already available and published, stress-test the obvious and non-obvious patterns of interaction (travel time by horse/donkey among known episcopal cities? Social networks of elite members as known from lead seals and written sources and epigraphy and likely connections to luxury items?) is the best way to stop repeating the same dull research questions over and over.

How can we move forward? These are difficult times, for foreign research projects and especially for Greek institutions. It seems unlikely that we will be able to work more, with more resources, on this and other related topics of Cretan history. Thus, our first aim should be to make our research more sustainable (no matter how much the term is abused): publish on the Web, encourage horizontal and vertical exchange of skills and knowledge among institutions, focus on research outputs that are reusable and continuously upgraded (and perhaps kill interim reports).

-

GQB 2015, day 7: Gortyna in the 8th century through a ceramic lens

On 16th July we’re headed to Rethymno for a workshop on Byzantine cities in Crete. Our participation was a last minute deal but I thought it would be useful to provide an overview on the entire city of Gortys, not limited to the GQB area, from the point of view of a ceramic specialist. What follows is a short summary of my talk. Tomorrow I will post a summary of the workshop and some conclusions about my own talk.

At Gortys, there is a recognisable occupation phase in the 8th century: we have evidence in the Pretorio, the Byzantine Houses and the Byzantine Quarter, the Pythion, the Mitropolis basilica, the Agora, possibly the Acropolis and even some rural sites such as the small farm of Orthipetra in the Mitropolianos valley and Chalara near Festos. In short, almost everywhere we’ve been excavating in the past 20 years we found evidence later than the 7th century, even without accounting for the prolonged use of some ceramic items.

Therefore our research question should not be whether the city is still alive in the 8th century but how we understand the life in Gortys by means of archaeological indicators such as ceramic finds.

In the past few years, we have collectively published ceramic and numismatic evidence that contradicts the traditional date of 670 AD for an earthquake – pushing some 50-60 years later a possible catastrophic event (some publications are shy about this, though). When we speak of the 8th century in Gortys it is useful to distinguish into a “long 7th century” that lasts until this event and the remaining decades of the 8th century, according to both the ceramic and numismatic evidence. The period after this event is usually mentioned as “VIII e IX secolo” mainly because we have to accomodate for the 826-829 AD date from the written sources about the “Arab” conquest of Crete. I’ll leave a discussion of the 9th century for a next occasion, but the same approach can be used.

Part of our issues with the 8th century derive from the impact that earlier works like Gortina II or Gortina V had on the following studies, with their typological approach. It is only recently that we have collectively started focusing on contexts as atomic units of study, at least in some cases.

The main ceramic indicators we have are:

- Globular amphorae

- Sovradipinta bizantina

- Late Mediterranean fine wares

- Cooking wares

- Glazed wares

- Chafing dishes

- Oil lamps

Urban areas

The Pretorio, Byzantine Houses, Byzantine Quarter and Pythion are best considered as a single area, that had its main focus on the “Strada Nord” which crossed the urban area. Lots of excavations here!

The Mitropolis basilica is the most important religious area of the city. Recent excavations on the outer part of the absidal area have given important evidence.

The Agora was excavated in the 1990s but only recently published. Apart from a significant amount of Medieval material, including Byzantine amphorae, there is a deposit (“C”) dated from this period, possibly from the same destructive event seen elsewhere in Gortys.

The Acropolis was excavated in the 1960s and saw only a small intervention in 2003. It took a few decades to realise that some of the decorated pottery identified as Minoan was in fact Byzantine. Without a reevaluation of the material, we are left with a weak basis to analyse the place that must have been the seat of the civil/military power from the late 7th to the 9th century, and only the occupation is certain, with architectural remains and at least one coin.

Main ceramic indicators

Globular amphorae are well known but on their own they provide little chronological detail. However, their recurring association with other indicators that have a more tight chronology is very interesting. Their source is commonly indicated as either Cretan or Aegean: we still lack a precise indication in this regard. Their abundance in this period all around Gortys, unparalleled by other amphora types, indicates that they were used primarily as a storage container, to stockpile liquids (wine?) in huge quantities – as much as 750 liters just in one building. Other amphorae that are quite numerous in this period are LRA 5/6 from Palestine and the Nile Delta region, and the LRA7 in some areas of the city.

The Sovradipinta bizantina is of limited interest as a general indicator for Crete, because it only circulates in the immediate vicinity of Gortys and only rarely found outside the Mesara. Its production starts at the end of the 6th century and goes on into the 7th and 8th century, apparently without any significant distinction in typology or decoration. Again, it is difficult to use this indicator alone to point to an 8th century date, even though ceramic evidence from the Praetorium points to a different chronology, mostly in the late 7th and 8th century. One thing is sure: the Sovradipinta bizantina was never meant to be a replacement for missing imports, since most of it is on closed forms like drinking cups, jugs, etc. that do not occur in the imported fine wares. Rather, we see decoration occurring on the formal repertoire of the local plain wares.

Traditionally, the end of trade in Mediterranean fine wares is dated at the end of the 7th century, to coincide at the very last with the Arab conquest of Carthage in 698. However, several authors agree that some productions could continue to be exported for some time in the 8th century, such as:

- the late African Red Slip D3 / D4, form 107 and 109 described by Bonifay;

- Late Roman D / Cypriot Red Slip, form 9B described by Watson;

- Egyptian Red Slip wares? We seem to have a consistent presence of Aswan ware, a production that is little known outside Egypt and is dated to to 7th century.

In general, cooking pots of this period are frequently bag-shaped, in coarser, more fragile fabrics. Cooking pots made on the slow-wheel appear sporadically, like a paradigmatic example of simplified ceramic production or even a comeback of domestic modes of production – at the same time they challenge our stereotyped view of pottery as typology and require a technological study that goes beyond traditional archaeometric provenance analysis. It is difficult to tell whether there were different cooking habits since most publications lack the level of detail that is needed, such as which parts of the cooking pot have traces of fire exposure, which have traces of dipper / κουτάλα, etc.

Glazed wares (the “Glazed White Ware” series 1) are the most recognisable finds of the period. While the coarser glazed cooking pots date already from the mid-7th in Constantinople, their fine counterparts seem slightly later according to the studies of Hayes. Some 9th century examples were already known since the 1980s in Gortys, but recently we have been finding more examples including the beautiful 8th century chafing dish decorated with fish and palm tree. Other known examples from Crete are from Pseira and Itanos. They could be interpreted as luxury items, but as with the imported wares we should be cautious to make an equation between archaeological rarity and actual social/economic value, since this production is very rare all over the Byzantine Empire.

Chafing dishes / σαλτσάρια come also in coarse fabrics, at least in two separate contexts from the BQ and the Agora. Since we have so few examples of this type, it is useful to see that the culinary habits linked to this new type of cooking vessel are not limited to glazed dishes (that could easily be gifts or decorative items). There’s room for discussing the fact that this habit appears in Gortys at the same time as other important centres of the Byzantine Empire, with simplistic explanations like the military or new civil authorities.

Finally, oil lamps. The “juglet” lamps are well known, especially type I. It seems that type II could be more widespread in the later period. Lamps in this period are less standardised, but in Gortys we don’t see hand-made lamps of the simpler open types. A separate discussion is needed to take into account the impact of glass on lighting of interior spaces, and we still don’t have collected the necessary data from our excavated material.

Conclusions

I’d like to leave my conclusions blank for tomorrow’s post.

The cover image is an African Red Slip sherd, form Hayes 109B, in D3 fabric, photographed through a magnifying lens (GQB CER 746.2).

-

GQB 2015, day 5: substitute

I’m a substitute for another guy

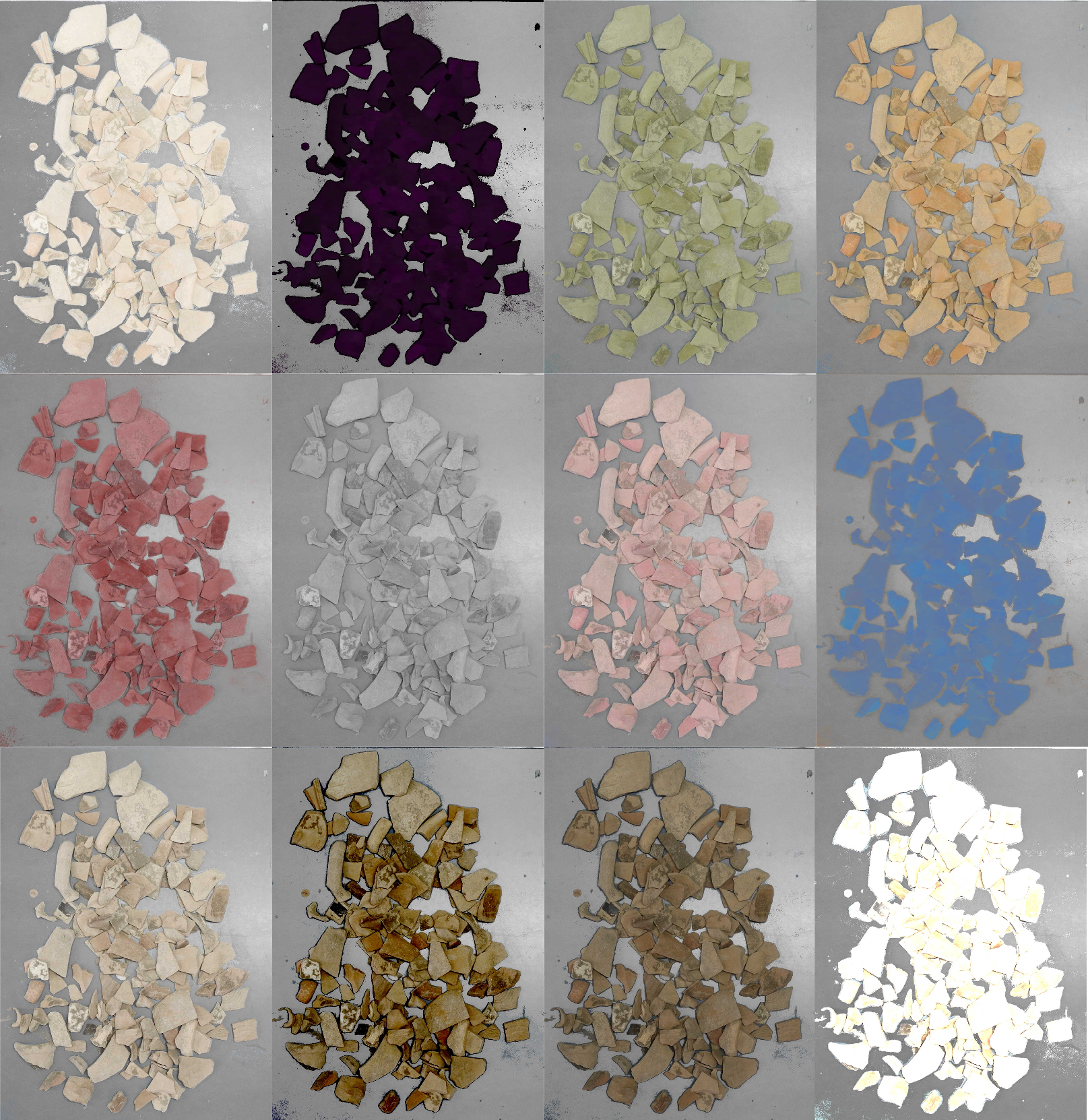

I look pretty tall but my heels are highAs I mentioned the other day, our team is in Gortys at the same time with the University of Padua team directed by Jacopo Bonetto. Since there is no ceramic specialist with them this year, they asked me to take a look at a few ceramic contexts from the Late Antique phase of the temple of Apollo (Ναός Απόλλωνος) where they excavated a few explorative trenches last year. This is what is normally called spot-dating: have a quick look at diagnostic finds from a context, identify whether there is enough material to provide a significant chronology and output a date range. Usually it is difficult to be very precise with less than 20-30 diagnostic finds, especially with local wares, and “first half of the sixth century AD” is good enough a starting point. Another recurring issue is with residual material, that is the norm in Mediterranean urban sites because small scraps of pottery as always found in the soil, sometimes centuries older than the date of formation. Residuality is an interesting phenomenon, too often overlooked or “analysed” in simplistic terms because it is rather difficult to model.

In detail, I’ve been looking at 5 contexts dated from the 3rd to the 6th century. The later ones are slightly larger and can be dated pretty reliably:

- in the mid-6th century you get African Red Slip Hayes 104A and LRC/Phocaean Red Slip Hayes 10A together with Aegean cooking wares;

- in the 5th century the most recognisable finds are local basins with a painted zig-zag decoration on the rim, a few sherds of Late Roman Amphora 3 and African Keay 25

- the earlier contexts are smaller, and more difficult to pinpoint with 1-2 diagnostic finds, either African Red Slip from the 4th century or Eastern Sigillata A from the early 2nd century.

All these are floor assemblages, resulting from prolonged use on top of landfills: the difference, in theory, is that a landfill should be dated to a single moment in time and can contain earlier material, while the floor deposit will contain small pieces subject to trampling and walking, ideally from the period when the floor was in use. This distinction is useful in theory but in practice floor surfaces tend to be slightly over-excavated and the finds are all from top part of the lower fill layer.

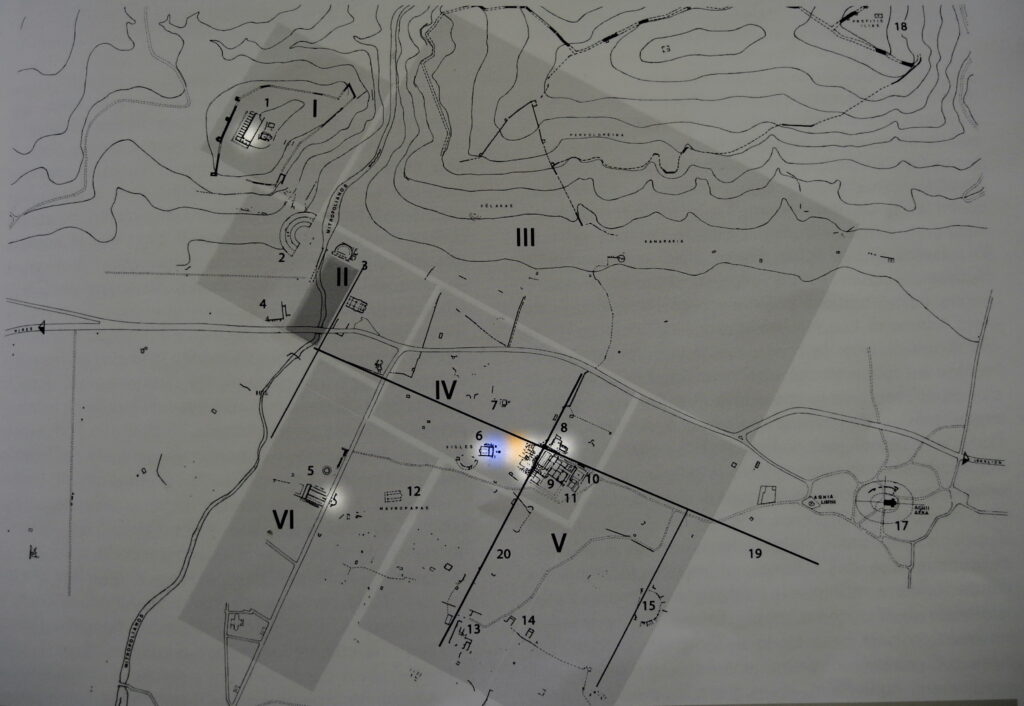

Archaeological map of Gortys: the bright areas are recent excavations with 8th century material; blue spot is the Pythion, orange spot the Byzantine Quarter. To my surprise, there were some beautiful and much larger assemblages from the 7th and 8th century that didn’t interest much to our colleagues from Padua, but were rather sweet for us Byzantine archaeologists! Apart from a very good selection of type-finds (Late Roman D/Cypriot Red Slip Hayes 9, juglet-shaped oil lamps, globular amphorae and their sibling water jars with one handle, Egyptian Red Slip dishes, cooking pots made on the slow wheel, etc) the context as a whole was both tremendously familiar and interesting, so similar to what we found in the nearby Byzantine Quarter / Βυζαντινή Συνοικία. The difference is in the BQ we see traces of people dwelling well into the 8th century, while houses in the Pythion area seem abandoned slightly earlier, thus we might be looking at glorious rubbish dumps from “our” side. It is truly worth a further look.

-

Archaeology in the Mediterranean: I don’t wanna drown in cold water

This post is the second half of the one I had prepared for this year’s Day of Archaeology (Archaeology in the Mediterranean: do not drown if you can). For an appropriately timed mistake, I only managed to post the first, more relaxed half of the text. Enjoy this rant.

Written and unwritten rules dictate what is correct, acceptable and ultimately recognised by your peers: it is never entirely clear who sets research agendas for entire disciplines, but ‒ just to be more specific ‒ I feel increasingly stifled by the “trade networks” research framework that has dominated Late Roman pottery studies for the past 40 years now. Invariably, at any dig site, there will be from 1 to 100,000 potsherds from which we should infer that said site was part of the Mediterranean trade network. We are all experts about our “own” material, that is, the finds that we study, and apart from a few genuine gurus most of us have a hard time recognising where one pot was made, what is the exact chronology of one amphora, and so on. But those gurus, as leaders, contribute to setting in stone what should be a temporary convention as to what terminology, chronology and to a larger extent what approach is appropriate. I can hear the drums of impostor syndrome rolling in the back.

I don’t want to drown in this sea of small ceramic sherds and imaginary trade networks, rather I really need to spend time understanding why those broken cooking pots ended up exactly where we found them, in a certain room used by a limited number of people, in that stratigraphical position.

At the same time, I’m depressingly frustrated by how mechanical and repetitive the identification of ceramic finds can be: look at shape, compare with known corpora, look at fabric, compare with more or less known corpora. If any, look at decoration, lather, rinse, repeat. My other self, the one writing open source computer programs, wonders if all of this could not be done by a mildly intelligent algorithm, liberating thousands of human neurons for more creative research. But this is heresy. We collectively do our research and dissemination as we are told, with sometimes ridiculously detailed guidelines for the preparation of digital illustrations that end up printed either on paper or on PDF (which is the same thing). Our collective knowledge is the result of a lot of work that we need to respect, acknowledge, study and pass on to the next generation.

At the end of the obligations telling you how to study your material, how to publish it, and ultimately how to think about it, you could just be happy and let yourself comfortably drown into the next grant application. Don’t do that. Do more. Follow your crazy idea and sail the winds of Mediterranean archaeology.

-

L’Italia in Africa: Pietro Toselli, Amba Alagi e il “solito” piatto in ceramica

Quando due anni fa ho pubblicato su questo blog un racconto iper-dettagliato su alcuni piatti marchiati Società Ceramica Italiana non avrei mai pensato che quel racconto sarebbe diventato di gran lunga la pagina più visitata di questo piccolo blog. Era inaspettato, mi ha messo in contatto con altre persone molto più competenti di me sull’argomento, ma soprattutto mi ha incoraggiato a coltivare l’interesse verso le ceramiche di età contemporanea. Oggi vi racconto una storia un po’ meno personale ma abbastanza simile e altrettanto interessante.

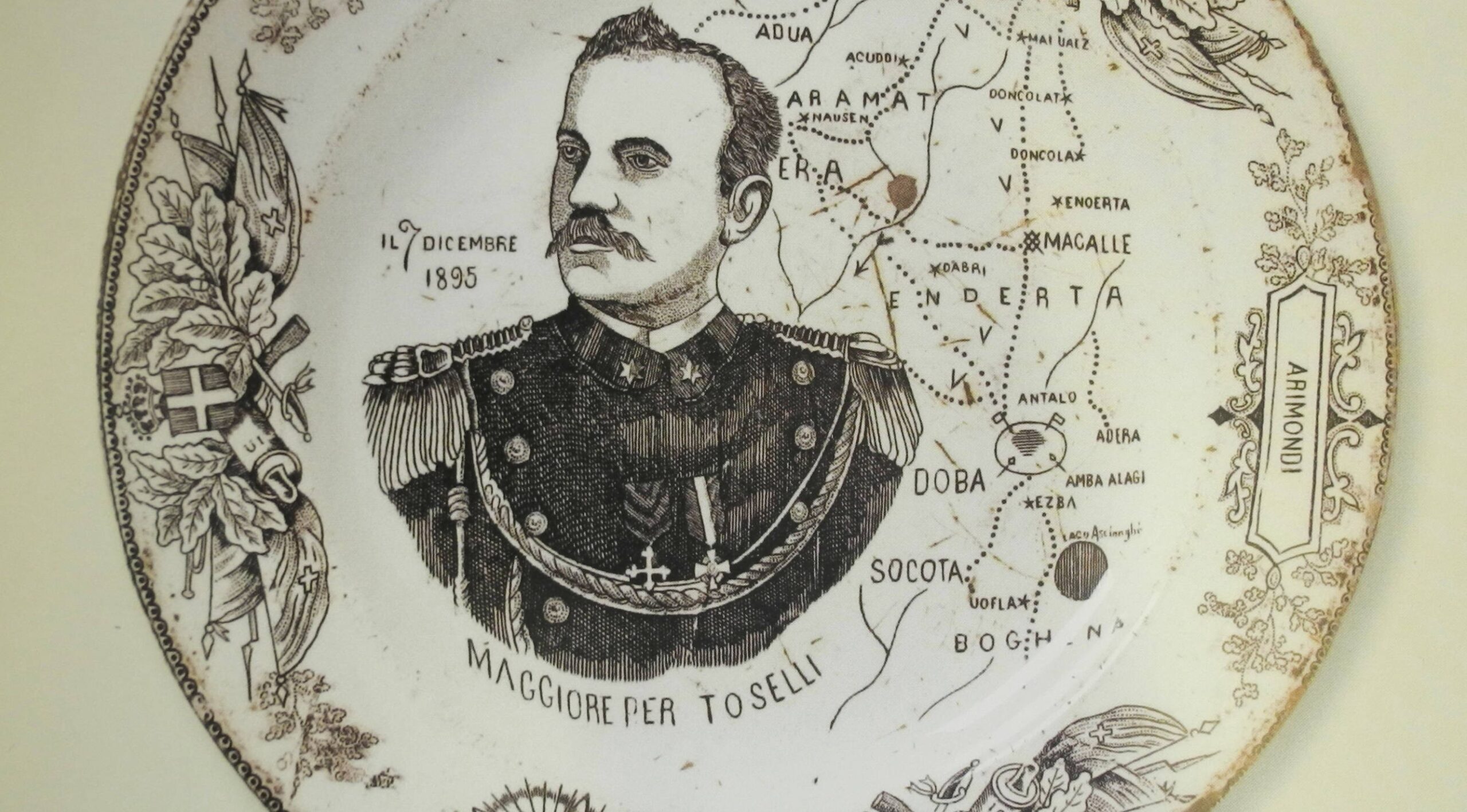

Parliamo di un piatto prodotto a Mondovì dalla manifattura Alessandro e Cesare Musso tra il 7 dicembre 1895 e il 1 marzo 1896. Non è molto frequente avere una indicazione cronologica così precisa per la produzione di un manufatto industriale di massa ‒ e si tratta di una cronologia indiretta ma rigorosa. Ma andiamo con ordine.

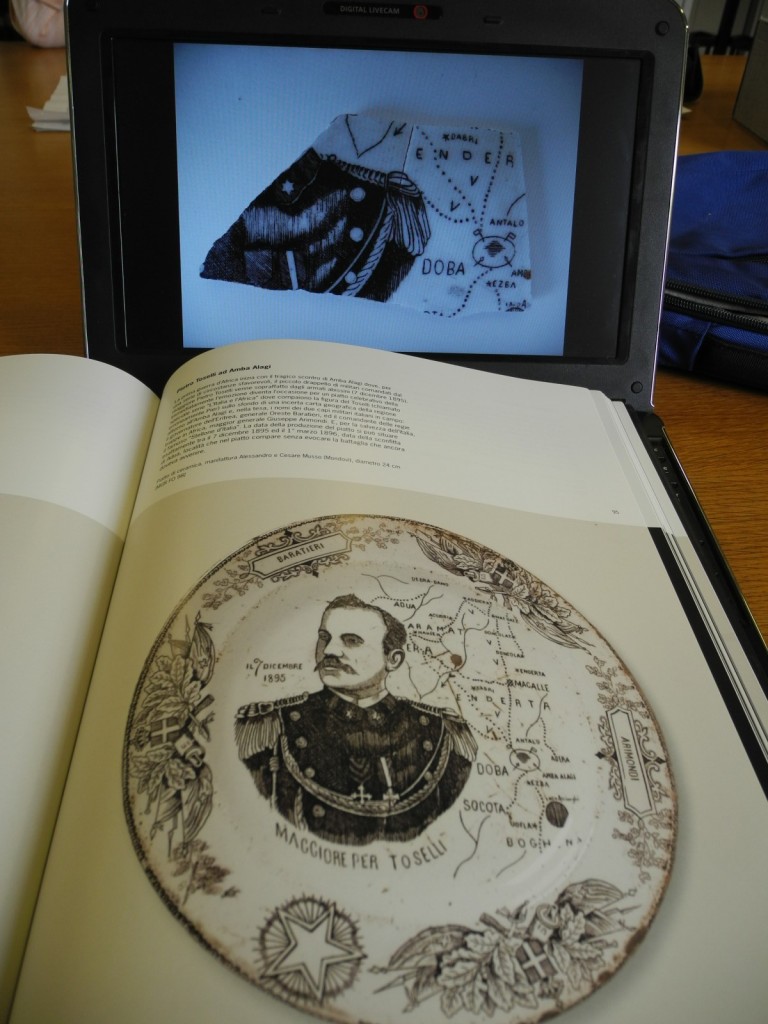

La scorsa primavera ho riordinato per lavoro alcuni reperti in ceramica provenienti da uno scavo urbano effettuato a Oneglia tra 2010 e 2011 ‒ con una documentazione fotografica preliminare. Un lavoro molto semplice e ovviamente superficiale. Non potevano comunque sfuggirmi i due frammenti di questo piatto, che raffigurano una divisa militare e una approssimativa carta geografica con nomi chiaramente etiopi come Doba, Ender[a], Ezba, Amba. Su un frammento della tesa si legge “maggiore”. Vi basti che stavo leggendo Point Lenana proprio nello stesso periodo.

Ho cercato un po’, ho trovato il libro Ceramiche patriottiche e militari dell’Italia contemporanea di Roman H. Rainero (edito nel 2008) e ho deciso che lì potevo trovare qualche notizia in più. Il libro non è molto diffuso ma l’ho trovato nella bellissima biblioteca dell’Istoreto di Torino. E nel libro ho trovato il piatto, ovviamente.

In biblioteca all’Istoreto con il libro e le foto del piatto Il piatto è stato prodotto dalla manifattura di Alessandro e Cesare Musso a Mondovì, come indicato nel marchio a inchiostro. Questa manifattura non compare nell’Archivio della ceramica italiana del ‘900, forse perché chiuse i battenti a fine Ottocento, ma è probabilmente collegata alle altre manifatture Musso di Mondovì. Il piatto porta una decorazione dedicata (stranamente) alla commemorazione di un evento negativo per l’Italia: la disfatta di Amba Alagi durante la guerra abissinica, in cui perse la vita il maggiore Pietro Toselli (a cui sono intitolate vie in moltissime città d’Italia, non ultima Siena). La data di produzione è necessariamente compresa tra il 7 dicembre 1895 (data della battaglia) e il 1 marzo 1896, cioè la data della sconfitta ben più disastrosa di Adua, che compare invece in posizione defilata nella approssimativa carta geografica alle spalle di Toselli. Nel frattempo c’era stato anche l’assedio di Macallè, celebrato in altri due piatti della serie “L’Italia in Africa” molto simili anche nella decorazione.

Preciso subito che non conosco il valore di mercato di questo piatto, nel caso in cui ne possediate uno intero (dubito che in frammenti sia di interesse per i collezionisti). Ho l’impressione che non ve ne siano molti esemplari in circolazione, probabilmente a causa del breve periodo in cui è stato prodotto, ma posso sbagliarmi.

Da archeologo, lasciando da parte il piatto intero e tornando ai frammenti, devo sottolineare che questo reperto va considerato nel suo contesto di rinvenimento, in cui erano presenti altri oggetti prodotti a Mondovì nello stesso periodo. È certamente molto raro trovarsi di fronte a un reperto ceramico con una datazione così ristretta, che spesso è rara anche per una moneta. Spero ovviamente che tutto il contesto venga pubblicato (per chiarezza: non me ne sto occupando), sarà molto interessante e darà una prospettiva meno ristretta alle osservazioni su che ho raccolto qui.

D’altro canto, non posso non domandarmi che significato ha avuto questo piatto per chi lo ha comprato e posseduto: persone senza nome ma certamente affascinate dall’impresa coloniale italiana, come tante altre in quegli anni. Certamente non tutti condividevano questo entusiamo, né era da tutti acquistare questi oggetti celebrativi da esporre nelle proprie case. Negli stessi anni sempre a Mondovì si producono oggetti in ceramica tesi a raffigurare gli etiopi con fattezze mostruose e animalesche, come a rafforzare l’idea della loro inferiorità. Sarà poi il regime fascista a condurre per alcuni anni l’Etiopia sotto il dominio italiano.

♦

Riporto alcuni brani del libro, ricordando che se siete interessati a questo argomento potete comprarlo direttamente dal bookshop del Museo Storico Italiano della Guerra o cercarlo in biblioteca.

La descrizione del piatto (pagina 95):

Pietro Toselli ad Amba Alagi. La prima guerra d’Africa inizia con il tragico scontro di Amba Alagi […] Immediatamente l’emozione diventa l’occasione per un piatto celebrativo della speciale serie “L’Italia e l’Africa” dove compaiono la figura del Toselli (chiamato erroneamente Pier) sullo sfondo di una incerta carta geografica della regione attorno all’Amba Alagi e, nella tesa, i nomi dei due capi militari italiani in campo: il governatore dell’Eritrea, generale Oreste Baratieri, ed il comandante delle regie truppe in Africa, maggior generale Giuseppe Arimondi. E, per la salvezza dell’Italia, il famoso “Stellone d’Italia”. La data della produzione del piatto si può situare esattamente tra il 7 dicembre 1895 ed il 1° marzo 1896, data della sconfitta di Adua, località che nel piatto compare senza evocare la battaglia che ancora doveva avvenire.

Piatto di ceramica, manifattura Alessandro e Cesare Musso (Mondovì), diametro 24 cm [MGR FO 98]

La serie “Italia in Africa” fu comunque un successo effimero (pagina 97):

La serie ”Italia in Africa”. Il positivo esito di vendita dei piatti di Toselli e di Galliano indusse la manifattura ad inaugurare una vera serie di “piatti coloniali” dell’Italia, nella speranza di proseguire le fortunate produzioni. Ma questo progetto non andò molto avanti, forse per le infauste sorti della guerra, e così lo speciale marchio della serie di Toselli e di Galliano su “L’Italia in Africa” non annoverò la produzione di altri piatti.

Le manifatture ceramiche italiane sono schierate con le autorità (pagina 17), e questo fa riflettere sull’estrazione sociale degli acquirenti di questi piatti:

le produzioni italiane appaiono stranamente diverse da quelle rivoluzionarie francesi in quanto non celebrano mai eventi “sgraditi” alle autorità e a una certa parte dell’opinione pubblica. […] si trovano celebrate persino sconfitte clamorose (Amba Alagi, Macallé) ma mai momenti di lotta dell’“altra” Italia, quella che pareva non degna di fare storia ufficiale.

Alla prossima puntata.

-

Spark plugs and archaeological finds: where do the ethics of fieldwork stop?

Yesterday I posted a picture of a crate with sherds of Roman pottery and a spark plug. That was fun to find and look at, because of course a spark plug is an out-of-place artifact among archaeological finds. Or rather, it is not at all.

As Lewis Binford would argue, both Roman pottery and the lonely spark plug live in the present, regardless of when they were made. Archaeologists like to think of storage buildings as “sacred” spaces of cleanliness, order and rest for the countless finds we unearth every day. That’s what manuals prescribe, so it must be like that. However, as anyone who has seen some of these rooms filled with crates and boxes knows, disorder and dirt is the rule, not the exception. There is rarely, if ever, a clear-cut separation between storage of finds and working tools, or in the best cases between storage and display. Corridors are always blocked by other crates that couldn’t find a place on the shelves. Finding where one specific crate is may take one minute, but it is always pulling it out that will keep you busy for ten or fifteen minutes. All this provided that proper archive records exist and that you can get a list of where things are, and that may prove difficult or even impossible, regardless of who is in charge of producing such a list (heck, you may be responsible in most cases). That spark plug is not there to annoy or bemuse, it is just a gentle reminder that labels and clean sherds do not stop things from happening, objects from moving (shelves collapsing, crates of any material rotting away and breaking) and people interacting with them all the time. There you have it, a storage room filled with archaeological finds is a living context, and one that should not look unfamiliar to an archaeologist.

Me with a dust mask. Is that enough for punk archaeology? On the back, the usual suspect crates of finds. Sub-optimal working conditions, uncontrolled temperature (both cold and hot), dust everywhere, need to move heavy loads: this list may be just a random sample of the small everyday glitches of archaeological fieldwork … including that of the finds specialist, and of the assistant to the finds specialist, and of the person working to keep that sacred space clean and accessible (whatever their job is called).

There is an hopefully increasing consciousness of the beauty and significance of “digging the dirt” (best exemplified by works as Between dirt and discussion by Gavin Lucas) in archaeological fieldwork. Dirt is qualifying archaeology, and attempts to leave it out of archaeological discourse are demeaning. No matter how much you clean them, potsherds are still pieces of fired clay found in the soil. Let us bring more of that consciousness out of the trenches, because in the end the substantially boring nature of our work is the same.

Crazily enough, I am discussing most of the above in my dissertation.