Un mese fa, pochi giorni dopo essere rientrato dall’incontro FOSS4G-IT di Padova, ho mandato una email a un gruppetto di 8 persone che, presenti fisicamente o meno a Padova, hanno seguito da vicino le vicende di ArcheoFOSS negli ultimi tempi. Con questa email ho salutato ArcheoFOSS e adesso, sedimentati un po’ i pensieri, pubblico questo articolo con un augurio di buon viaggio.

L’edizione 2019 di ArcheoFOSS è stata ottima, sia dal punto di vista degli interventi sia come partecipazione numerica ai workshop. Ha funzionato abbastanza l’integrazione con gli amici di FOSS4G-IT, nonostante una certa ghettizzazione (aula lontana, niente streaming, niente computer pronto) di cui è rimasta traccia anche nei comunicati stampa conclusivi e nelle discussioni organizzative di coda. Non ho comunque potuto fare a meno di notare negli interventi un certo distacco tra chi presenta in modo occasionale e chi ha seguito negli anni un percorso collettivo di crescita, tra chi ha “usato l’open” e chi costruisce strumenti condivisi, conoscenza trasversale.

Gli incontri però non si chiudono con la fine dell’ultima presentazione in sala. Come abbiamo detto a Padova, con grande sforzo mio, di Saverio Giulio Malatesta e soprattutto di Piergiovanna Grossi sono quasi ultimati gli atti del 2018 che saranno pubblicati in un supplemento di Archeologia e Calcolatori grazie alla disponibilità di Paola Moscati e alla volontà di tanti autori di autotassarsi per contribuire alla pubblicazione del volume.

Ma veniamo al dunque.

Condivido una decisione che ho maturato serenamente negli ultimi 6-12 mesi, cioè quella di fare un passo indietro e “uscire” da ArcheoFOSS per la prima volta dal lontano 2006 a Grosseto (quando non avevamo ancora questo nome, ma uno molto più lungo). Questo non perché io non condivida lo spirito che anima questo gruppo di persone, che anzi credo di continuare a coltivare e diffondere. Né perché io sia “arrivato” a occupare una posizione in soprintendenza dove non ho più bisogno di ArcheoFOSS come biglietto da visita (non che sia mai successo…).

Vorrei metaforicamente uscire dalla porta dopo aver salutato, a differenza di tante altre persone che hanno fatto anche molto (penso a chi ha organizzato il workshop nelle edizioni 2006, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013) senza poi avvisare in modo chiaro di non essere più a bordo.

Semplicemente, se così posso dire, mi manca il tempo per fare con entusiasmo e passione le cose indispensabili (organizzare il workshop, pubblicare gli atti, ma anche tenere il tutto vivo per 12 mesi l’anno, gestire il sito, il forum) e non ho le energie per farle nemmeno in modo approssimativo. Non è l’unico impegno di questo genere che ho deciso di chiudere (a breve, per gli affezionati, altri aggiornamenti).

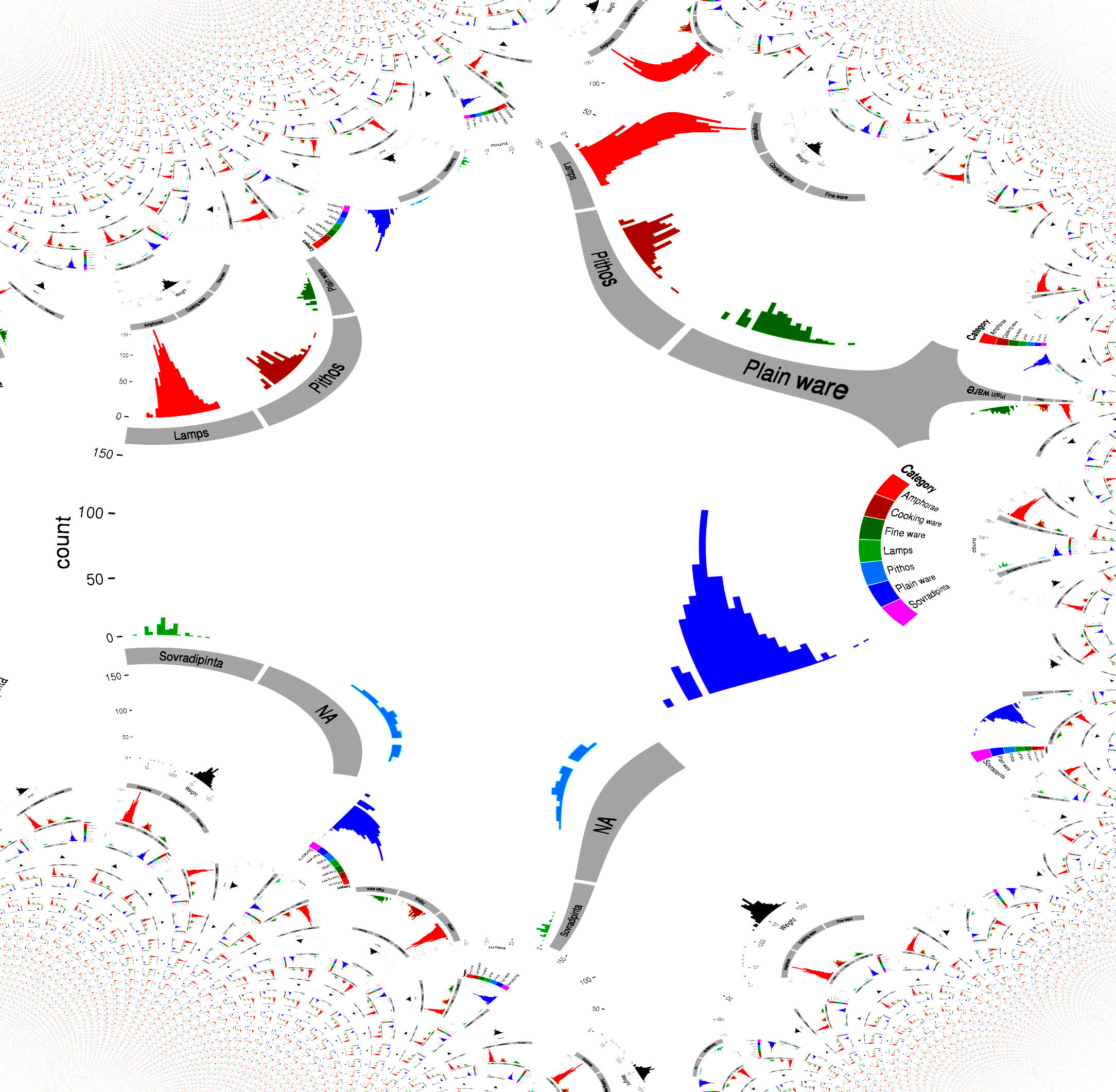

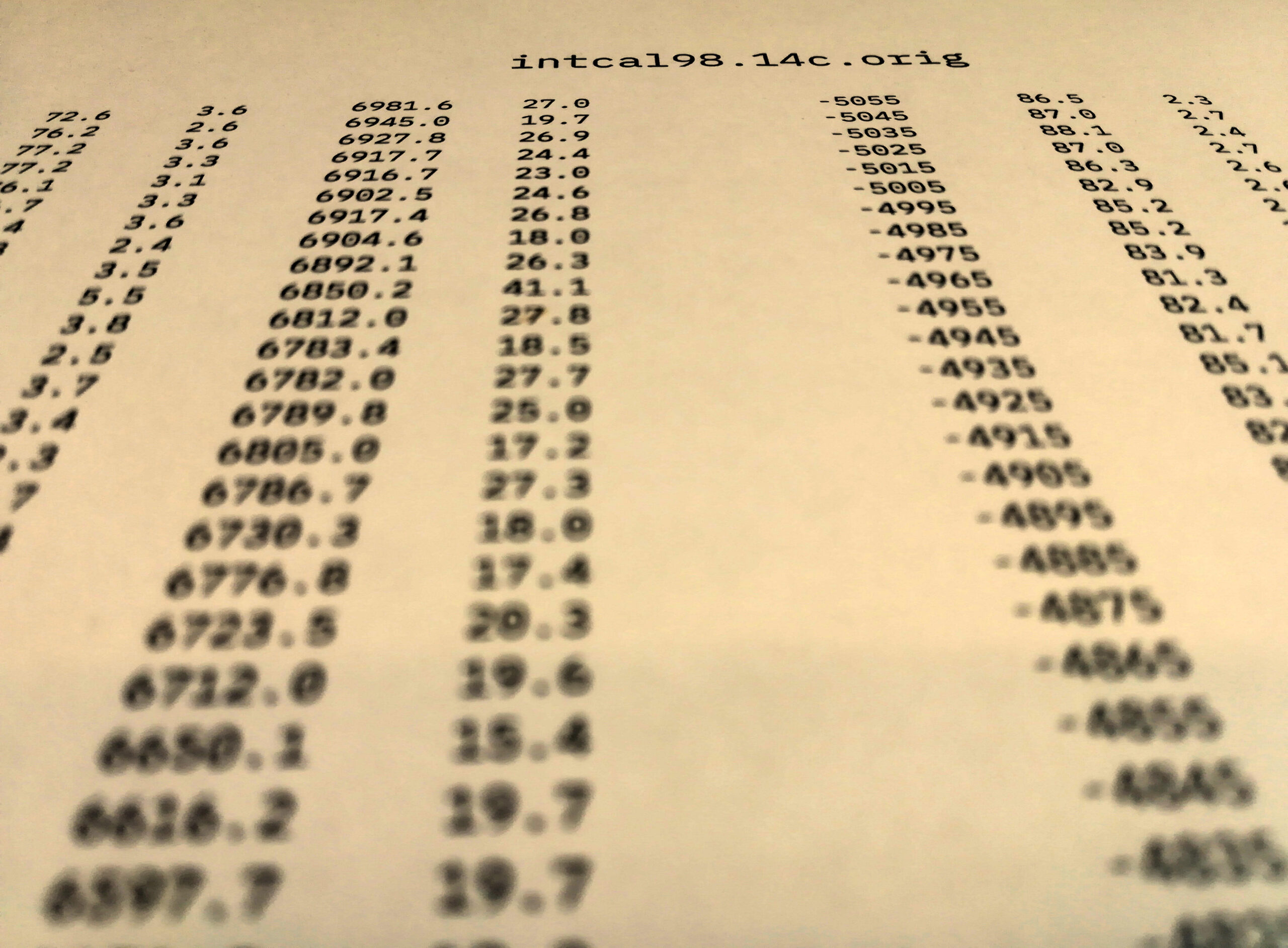

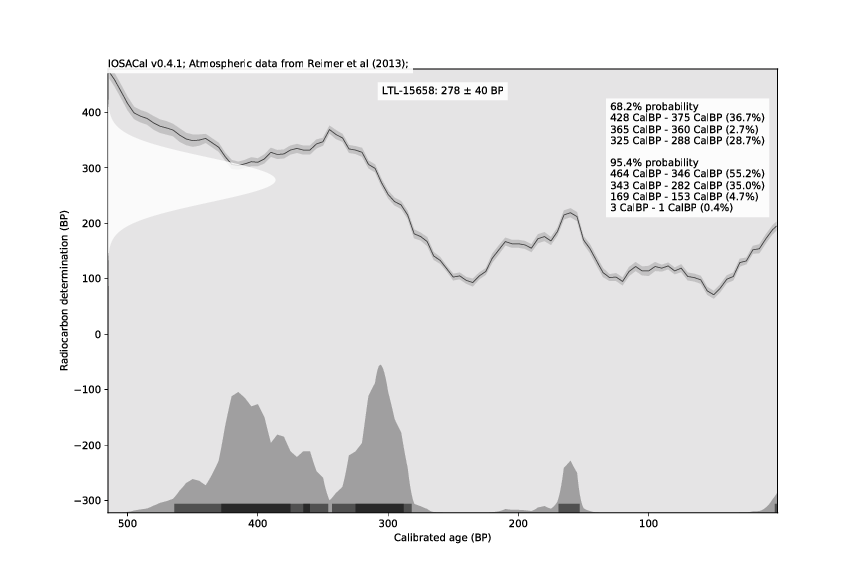

ArcheoFOSS mi piace sempre moltissimo, anche se mi sembrano sempre più flebili l’anima quantitativa, quella metodologica, quella di rivendicazione che proprio nel 2006 erano un ingrediente fondamentale. Senza quelle, io penso che non si vada lontano. Penso anche che ArcheoFOSS troverebbe uno spazio più coerente a rapporto con realtà e incontri archeologici invece che recitando la parte “archeo” di un altro contenitore legato al software libero (perché così manca un confronto critico, una valutazione sulla bontà archeologica dei lavori presentati, e soprattutto la possibilità di incidere direttamente sulla pratica del settore). Questo ovviamente vale nella situazione attuale, in cui non ci sono risorse per organizzare un incontro autonomo.

Passando alle questioni pratiche, come avevo anticipato, ho chiuso il forum Discorsi su ArcheoFOSS lasciando in sola lettura i contenuti pubblici. Questo ha suscitato una “lettera aperta” da parte di Emanuel Demetrescu, che dopo averla condivisa con me ha voluto pubblicarla anche su Facebook, non so con quale riscontro.

Inoltre ho deciso che non farò parte del comitato scientifico per prossimi incontri.

Mi piacerebbe moltissimo partecipare in futuro ad ArcheoFOSS presentando quello che credo di continuare a fare (software libero, banche dati, formati aperti). Quando è iniziata questa avventura avevo 23 anni e adesso ne ho quasi 36: non esagero dicendo che ho imparato moltissimo dalle tante persone che ho avuto la fortuna di incontrare in questi anni, e ne sono pubblicamente e dichiaratamente riconoscente. Ci incontreremo ancora.

Nel frattempo, vi auguro buon viaggio.