Questa è la solita rubrica che scrivo da molti anni. Ci sono quindi delle puntate precedenti per chi volesse leggerle, non sempre brillanti e non sempre cose che riscriverei oggi.

Quest’anno per la prima volta mi sono reso conto che scrivere solo la lista dei libri sarebbe stato un po’ riduttivo, perché ho fatto altre cose di categoria “consumi culturali” e non mi piacciono troppo le barriere artificiali. Perché dovrei elencare un libro brutto ma non dire niente di un podcast che mi è piaciuto e di una mostra per cui mi sono messo in viaggio? O perché dovrei fare tanti articoli separati per ogni categoria?

I libri che mi sono piaciuti

Avevo iniziato l’anno leggendo L’incendio di Cecilia Sala e Tutta intera di Espérance Hakuzwimana. Il primo mi è piaciuto ma non in modo esagerato, in vari punti e soprattutto nei capitoli dedicati all’Ucraina mi sono reso conto di non essere il destinatario di questo libro, di non fare parte del “noi” collettivo in cui l’autrice ci butta tutti dentro per farci capire la distanza siderale tra l’Italia e i tre paesi in cui ha lavorato (Iran, Ucraina, Afghanistan). E non ne faccio parte un po’ perché alcune delle cose che il libro racconta già le conosco da tempo (perché gli iraniani odiano gli USA…) e so già cosa non va in quello che “gli italiani” nel loro insieme sanno, nel modo in cui lo stato italiano si pone rispetto a tutte queste altre nazioni. Almeno sapevo qualcosa su Cecilia Sala quando è stata imprigionata, sul suo rapporto con l’Iran.

Tutta intera ha molte sfaccettature. Il libro inizia in modo lieve e poi come un tamburo di guerra inizia a fare sempre più rumore, a narrare le lacerazioni del “fiume calmo” che la protagonista via via prova su se stessa e sul gruppo di ragazzə che, prima a sua insaputa e poi sempre più alla luce del sole le faranno da guida. Una storia vivida di razzismo sulla propria pelle, di una ricchezza umana (e quindi culturale, nel senso più nobile di cultura) che noi, quelli “tutti interi”, non ci sogniamo nemmeno da svegli. La scansione temporale dei capitoli è studiata in modo accurato e le ultime pagine lasciano senza fiato per la ferocia e la speranza che suscitano.

Raja Shehadeh : Dove sta il limite. Attraversare i confini della Palestina occupata

Questo libro era in casa da qualche anno, già letto da Elisa. Leggerlo nel 2024 è solo leggermente più assurdo, insensato, mentre lo sterminio del popolo palestinese prosegue senza sosta con la connivenza di tanti Stati occidentali. La finestra di tempo è sempre la stessa, l’unica con cui si può guardare quella parte di mondo, e inizia nel 1948.

Silvia Avallone: Acciaio

Incredibile, veramente incredibile.

Riuscire in mezzo a queste pagine a stare male, malissimo per la tragedia smisurata che vivono le persone, tutte a modo loro protagoniste. Riuscire a gioire con le lacrime agli occhi per le loro felicità, il loro amore…

Mi ha fatto male solo cercare in rete il nome dell’autrice e scoprire che ha esattamente l’aspetto che mi immaginavo per una delle due protagoniste. Ha reso in qualche modo ancora più lucido tutto il profondo senso di realtà e di umanità.

Come in Cuore nero ho trovato toccante il racconto finemente tessuto di una adolescenza viva, piena, dolorosa e al tempo stesso carica di felicità incontenibile. Mi tocca anche leggere nero su bianco le strade che si dividono nei percorsi scolastici e di vita. Le vite spezzate per sempre e quelle spezzate da sempre nel logorio della provincia (come Tre).

Mi ricordo quando passavo parecchio tempo vicino a Piombino ed era uscito questo libro. Come sempre senza un motivo, non l’ho letto e non mi sono nemmeno domandato se mi potesse interessare. Ogni cosa ha il suo tempo, anche i libri. Anche le navi.

Laura Pugno : Sirene

Inquietante e meraviglioso. Mi è piaciuto il tema apocalittico tessuto tra biologia e psicologia. Mi è piaciuto che sia un racconto distopico con elementi fantastici. Ho trovato ripugnante il modo in cui la Yakuza e soprattutto gli uomini sguazzano in un potere cruento e senza limiti, ripugnante il modo in cui le donne sono trattate come merce.

E le sirene: incredibili creature, descritte in modo un po’ preciso e un po’ vago, con questo comportamento riproduttivo che mette in posizione dominante le femmine/madri. Mi ha colpito il modo inquietante in cui attirano tuttə lə umanə, in cui mandano in tilt sia le élite dominanti che smaniano per controllarle sia i gruppi marginali che vorrebbero difenderle.

Samuel mi è sembrato mosso da dolore e follia, la sua parabola è in gran parte crudele e assurda ma nel finale compie un sacrificio che mo è sembrato purificatore. È una figura tragica, disperata.

Victoire Tuaillon : Fuori le palle. Privilegi e trappole della mascolinità

Un libro potentissimo, pesante, faticoso, doloroso, indispensabile, scritto in modo scorrevole e fa venire voglia di ascoltare il podcast. Mi è dispiaciuto solo che si affronti poco, a maggior ragione nella bella traduzione “critica” italiana, il ruolo della religione cattolica.

Neige Sinno : Triste tigre

Dolorosissimo. Via via che il testo prosegue è sempre più immenso. nel libro è descritto molto bene il muro che separa chi sa di avere sempre dalla sua il privilegio di essere al sicuro, e chi sa di essere sempre in pericolo. È un muro intersezionale.

Valerie Perrin : Tre

Erano anni che volevo capire cosa stava dietro la copertina di questo libro, un autentico best seller. E sono contento di averlo finalmente letto. C’è la provincia, la fuga dalla provincia, essere sfigatə ma avere chi ti vuole bene, tenersi dentro segreti più grandi di te per troppo tempo, i corpi delle ragazze e dei ragazzi. Fare musica. Non mangiare animali. Insomma, mi è piaciuto moltissimo! I protagonisti hanno la mia età attuale, c’è musica a pacchi, adolescenza perduta. Ci ho trovato tanti legami con Cuore nero.

Silvia Avallone : Cuore nero

Questo libro è veramente molto intenso, gonfio di purezza, liberatorio per come ad ogni pagina si smonta qualcosa di rotto per farne altro. Ho pianto almeno 30 volte durante la lettura. La costruzione della cronologia alternata tra passato e presente, che ormai è un tratto distintivo di tanta narrativa, è molto raffinata.

A tratti ho pensato che sia più sincero sulla montagna questo romanzo di tanto Cognetti.

Viola Ardone : Grande meraviglia

Ho visto Oliva Denaro nella trasposizione teatrale, ma è il primo libro di Viola Ardone che leggo. L’ho trovato molto toccante e commovente, soprattutto per la fragilità del protagonista.

Mario Lodi : Il paese sbagliato

Un libro che ho conosciuto tramite Sandro Ciarlariello e che mi interessava molto visto che ho due figli all’inizio del percorso di scuola. È una vera bomba, accurato, un testo politico di altissimo livello e il racconto di una scuola come poteva essere.

bell hooks : la volontà di cambiare

Il libro è di lettura scorrevole ma la forma risente molto del modo in cui sono scritti i saggi in inglese americano (un po’ come ho notato per David Graeber). Quindi la stessa frase torna più volte nel giro di poche pagine. Il contenuto di questo libro è una bomba e non stupisce che sia rimasto fino a poco tempo fa non tradotto. Andrebbe contestualizzata meglio la figura dell’autrice, perché solo dopo un po’ si capisce la profondità della condizione intersezionale di donna nera, il rapporto conflittuale con il femminismo bianco. Questo è un libro scritto per gli USA e quindi alcuni concetti presentati come universali sono forse un po’ zoppicanti altrove, ma è comunque un riferimento importante. Molte idee sono le stesse promosse dall’associazione Maschile plurale, che ho sentito sul podcast di Internazionale qualche settimana fa. Molte sono quelle raccontate dal padre di Giulia Cecchettin. Il libro parla di tanti aspetti di mascolinità tossica che mi riguardano, soprattutto nel rapporto tra genitori e figli. Ora io sono il padre.

Ho finito il 2024 leggendo l’incommensurabile Solenoide di Mircea Cărtărescu. Piccola parentesi: erano anni che volevo trovare libri di narrativa romena ma per mia incapacità non ci ero riuscito. Quando c’è stata la premiazione del Nobel ho letto il nome di Cărtărescu tra i possibili vincitori, e mi sono subito messo a leggerlo.

Le mostre

A ottobre c’è stata una mostra sull’archeologia di Imperia a Imperia. Ci tengo molto perché l’ho fatta io insieme al mio ex collega Luigi Gambaro con un grande lavoro di tante altre persone. Non è durata molto ma è stata importante per la città.

A dicembre siamo andati a vedere una mostra di Tina Modotti a Bologna, e anche se lei è molto conosciuta non avevo mai capito attentamente l’importanza e la varietà della sua vita, come fotografa e non solo. Ne ho approfittato per andare a visitare anche quella su Dominique Goblet all’ex chiesa di San Mattia, che mi è piaciuta moltissimo, ho anche acquistato il volume pubblicato da Sigaretten.

I podcast

Per una parte del 2024 ho avuto degli auricolari bluetooth funzionanti, e ho ascoltato parecchi podcast: Antennapod dice che ho passato 97,6 ore ad ascoltarli.

Sicuramente quello più notevole è stato C’è vita nel Grande Nulla Agricolo, di cui ho ascoltato le prime tre stagioni in attesa della quarta. È un podcast indipendente ma molto curato, mi ha rapito subito per la colonna sonora che mi ha fatto venire in mente Fuga da New York, l’ambientazione nella provincia profonda, l’orrore in agguato nei vecchi misteri del paese tra personaggi assurdi e atterraggi alieni. D’altra parte sono cresciuto nel “paese dei marziani”…

Ho ascoltato Polvere, dedicata all’omicidio di Marta Russo. Non amo il true crime ma qui il tema principale si sdoppia tra una giustizia che non sa funzionare e decide di accanirsi su qualcuno che deve essere colpevole, e dall’altro il funzionamento intimo della nostra memoria, che è molto molto più fragile di quello che ci hanno insegnato a credere. È scritto molto bene.

TOTALE è un podcast “varietà” che affronta in ogni puntata un tema di attualità. Jonathan Zenti è molto bravo e pungente, riesce sempre a portare il discorso oltre i limiti che uno si aspetta all’inizio. Il tema portante è che se non ci salviamo dal capitalismo tutte insieme, il capitalismo continuerà la distruzione già in atto.

Love bombing lo avevo già iniziato negli anni precedenti ma ho proseguito l’ascolto. Non è un podcast semplice, perché le storie sono sempre dolorose e a volte l’unico “lieto fine” è quello di riuscire almeno a raccontarle, ma non sempre. Io ne raccomando l’ascolto perché affronta in modo serio, documentato e rispettoso temi molto gravi che ruotano intorno alla stima di sé, alla gestione delle relazioni tossiche in coppia o in gruppo, alla ricerca del benessere, senza distinzioni di genere, di età, o altro.

Sonar è un podcast de Il Post in cinque puntate sui cetacei e sui capodogli in particolare. Racconta molte cose interessanti sui modi di comunicare tra animali e cetacei in particolare, sul modo in cui per molto tempo questi animali sono stati sterminati fino a metterne in pericolo la sopravvivenza, sulle differenze di linguaggio tra diversi gruppi sociali e clan. L’ultima puntata sull’utilizzo dell’intelligenza artificiale per la comprensione del linguaggio dei capodogli mi ha lasciato un po’ perplesso.

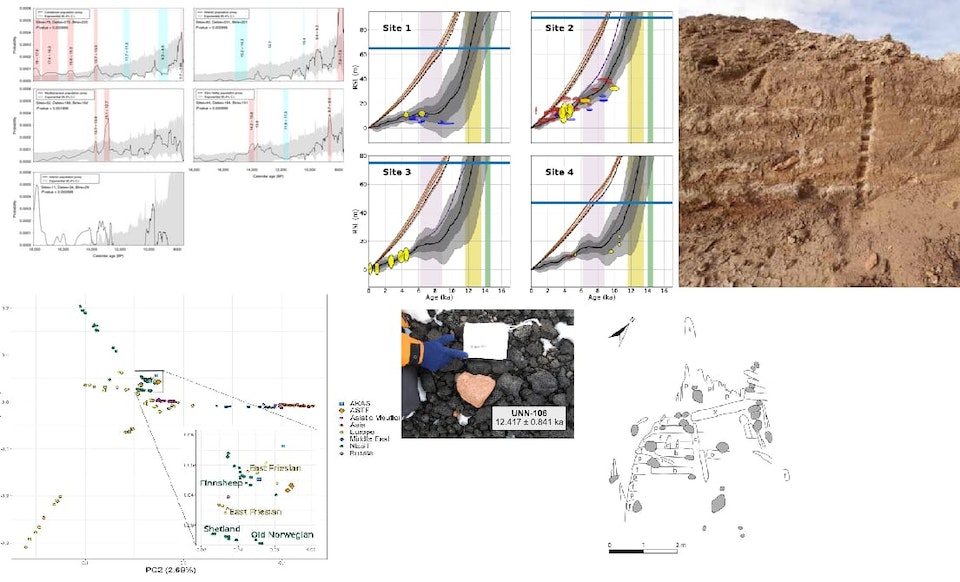

L’invasione è un altro podcast de Il Post, dedicato agli indoeuropei. Il titolo è molto forte, e secondo me è una scelta appropriata. Si sviluppa in cinque puntate tra archeologia, linguistica e genetica, tutte ben documentate. Lascia un po’ perplessi l’ultima puntata dove tutto quello che è stato raccontato sembra venire messo da parte per dire che in fondo gli indoeuropei si sono affermati in modo graduale e indolore (o comunque non più doloroso rispetto alle consuetudini del tempo), ma senza spiegare perché siano riusciti a cancellare quasi tutte le altre lingue della vecchia Europa. Insomma, per essere spiegato bene l’ho trovato un po’ inconcludente.

10 e 25 è un podcast di Slow News, a cui ho anche contribuito con una donazione. Parla della strage di Bologna del 2 agosto 1980, a partire dalle testimonianze di chi era lì, e poi via via si passa ai depistaggi, alle trame eversive dei fascisti, alla P2 di Licio Gelli e infine, ma non viene spiegato molto bene, anche della CIA (fatto che non può sorprendere nessuno), il più ampio dei “cerchi concentrici” che sono stati descritti dalla magistratura. Peccato che non ci sia una ultima puntata riassuntiva. C’è un archivio consultabile di tutti i documenti.

Ci sono poi alcuni podcast “correnti” come Il Mondo di Internazionale, Il giusto clima su Radio Popolare con Gianluca Ruggeri di ènostra, Stories di Cecilia Sala, il Nuovo baretto utopia di Kenobit. Tutti diversi, li ascolto spesso, anche se mai a cadenza fissa.

I film

Siamo andati al cinema a vedere Diamanti di Ozpetek, un regista che non mi piace particolarmente (da profano del cinema, i suoi film mi sembrano un po’ tutti uguali). Questo invece è molto particolare e potente, liberatorio.

Ho visto #likemeback su RaiPlay. Il film è ambientato lungo le coste della Croazia. Una vacanza estiva in barca tra tre ragazze italiane prende una brutta piega dopo la partenza spensierata. O forse la brutta piega era insita nell’incipit di un viaggio lontano dalla città, dalle famiglie e dalle altre amicizie ma costantemente rilanciato in rete tra social, stories, follower e compagnia. O forse la brutta piega è quella che hanno preso le vite delle persone di 20 anni o giù di lì, almeno questo sembra volerci dire il film. Vite schiacciate tra ansia da prestazione globale, paura di rimanere fuori e complessiva solitudine. E vite in cui essere giovani e belle non basta mai. I dialoghi misti in italiano e inglese creano una atmosfera strana e danno un ritmo tutto sommato lento, come le onde del mare.

Le serie

Non sono mai stato appassionato di serie.

Nel 2024 ho guardato Silverpoint, una serie per teenager a tema fantascienza e mistero. Episodi brevi, molto semplice e leggera, ma è simpatica.

Il teatro

A marzo abbiamo visto “Pa’”, uno spettacolo su Pierpaolo Pasolini, o forse sarebbe meglio dire con Pasolini. Luigi Lo Cascio interpreta Pasolini in versi e ossa. Non siamo arrivati molto preparati ed eravamo anche un po’ stanchi, ma lo spettacolo è intenso e, passatemi il termine, difficile. La recitazione è a ritmo serrato e in metrica: anche le frasi più semplici diventano piccoli scogli da scalare. Il percorso è autobiografico, da un momento antecedente al concepimento fino alla morte, forse oltre la morte stessa. Viene portato in scena un Pasolini molto intimo e profondamente lirico, anche quando questo si manifesta in modo eccessivo. Ma i passaggi politici, che ruotano intorno alla morte del fratello, sono potentissimi e tragicamente attuali.

Ad aprile abbiamo visto insieme Oliva Denaro. Ambra Angiolini è molto brava, e lo sapevo già ma non mi era ancora capitato di vederla dal vivo. È uno spettacolo forte e molto attuale.

In autunno ho visto Roberto Zucco, molto cupo e tragico. È un’opera complessa di cui non sono riuscito a capire tutto, avrei avuto bisogno di una spiegazione.

Infine ho visto La traiettoria calante. Uno spettacolo in forma di monologo che parla del crollo del Ponte Morandi a Genova. L’autore/attore è giovane e molto bravo, ma non mi è piaciuto molto il modo in cui veniva affrontata la tragedia, quasi da standup comedy.

I viaggi

Abbiamo visitato diverse città: Ravenna, Milano, Roma, Bologna, in modi e tempi diversi, qualcuna in giornata, altre per più giorni.

Abbiamo fatto una vacanza estiva in Corsica, l’ultima volta ci eravamo stati nel 2007.

Un po’ è un privilegio, si capisce, poter fare così tanti viaggi con tutta la famiglia. Un po’ anche una questione di priorità, per noi soprattutto conta andare in giro e vedere posti diversi e persone diverse, anche senza fare cose complicate.